Author: David Fekke

Published: 4/17/2021

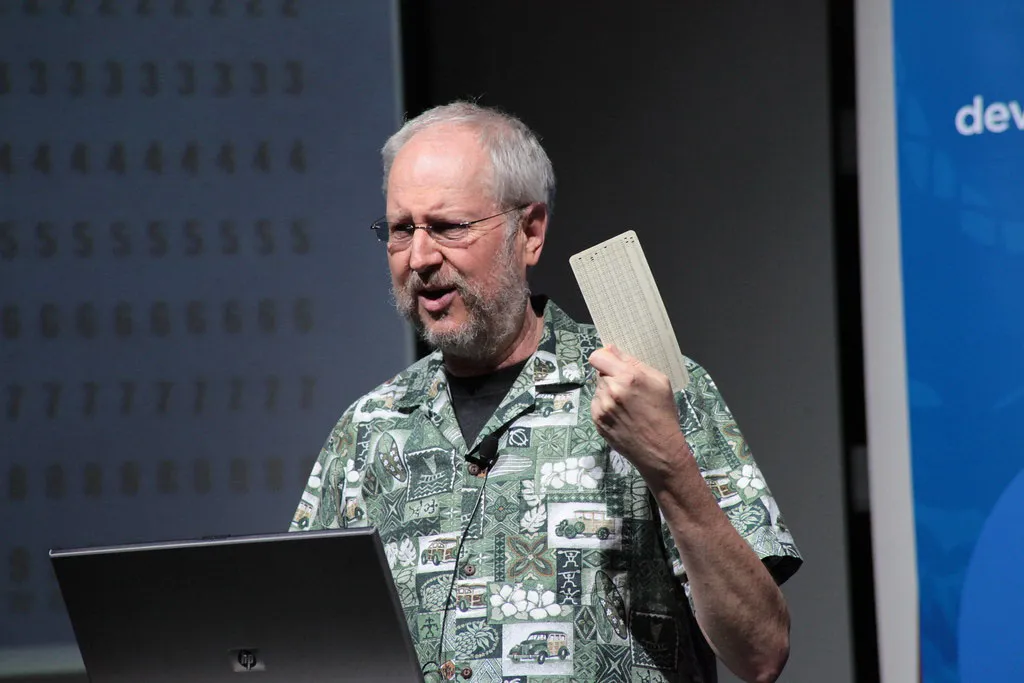

I recently wrote a post on the way I like to create objects in JavaScript. I call this style of object creation ‘Crockford Objects’, named after Douglas Crockford, author of “JavaScript: The Good Parts”.

I received a lot of feedback from people telling me that I did not explain why they should not use the ‘class’ keyword in JavaScript. I didn’t explain why because I was not saying that you can’t use it, I just prefer not to use the ‘class’ keyword for defining an object.

JavaScript is not an Object-Oriented Language

If you are familiar with the history of JavaScript, Brendan Eich was told they he was going to be able to write a scripting language for the Netscape Navigator to be based on Scheme. Scheme is a functional programming language. Then Eich was told that it had to look similar to Java, hence the name ‘JavaScript’. Oh, by the way, he only had two weeks to get it done.

So JavaScript was never intended to be an Object-Oriented language. It is actually a Prototype-Oriented language.

Douglas Crockford likes to joke that most developers who start using JavaScript never bother to actually learn the language first. And if you start looking at the language it has a lot of similiarities to Java and C#. In Java and C# you define classes as a template for a new object. In JavaScript, everything is an object.

Classes were added to JavaScript as a concession for C# and Java developers. Underneath the hood, the JavaScript engines still create objects the same way.

Binding

Binding is an issue that longtime React developers are familiar with in their applications. Objects defined with classes havto explictly use the this keyword. If you pass your class method to a callback, you can run into binding issues. This is why you will see a lot of code where the method has to be bound to the correct context. Lets take a look at an example;

class Thing {

constructor() {

this.myMethod = this.myMethod.bind(this);

}

myMethod() {

// Does something here

}

}

As you can see from the example above, the myMethod is being bound back to itself. To perform this function in the constructor, we have had to use the this keyword three different times.

Inheritance is bad

When I was first learning Object-Oriented programming, one of the three main features is inheritence. You can do this with the extends keyword by extending from a base class.

class Cat extends Animal {

// Body here

}

Under the hood in JavaScript this is done by a delegate to the parents prototype property. There are performance considerations with this type of operation, but that is not the main reason to avoid inheritance.

Even in true Object-Oriented languages, inheritance should be avoided. A common problem that developers run into with inheritance chains is the fragile base class problem. This is sometimes referred to the Gorilla/Banana problem. The main issue has to do with tight coupling to a parent object. If you need to make a change to the parent object, it is reflected down the entire tree of objects. I am currently working with a Java API where this is a huge problem.

Composition of objects in most cases is a better approach than inheriting from parent objects, even in Object-Oriented languages. In strictly typed languages like Java or Swift you are better off inheriting from an interface or a protocol than from a class. Also in Java and C# you can inherit from an Abstract class.

Encapsulation

Encapsulation is another feature of Object-Oriented programming that is actually a good feature. Te idea behind encapsulation is that we are able to hide the implementation details of our object by using data and methods that are only accessible from inside the body of our class. While it is possible to create private functions inside of a class by using the ’#’ character, we can not make variables private in JavaScript.

class APerson {

constructor(first, last) {

this.firstname = first;

this.lastname = last;

}

printName() {

console.log(`${this.firstname} ${this.lastname}`);

}

}

const somePerson = new APerson('David', 'Fekke');

somePerson.firstName = 'Bob';

somePerson.printName();

// Output: Bob Fekke

As you can see from the example above, we set the all of the properties in our class from outside the class. This violates one of the key principles Object-Oriented programming.

React

React is one of the front end frameworks I have used, and they recently made a change to the default way they create components. Previously in React you would create a class that extended React.Component. When React 16.8 was released they added a new feature called ‘Hooks’. If you need to manage state in your component, you would use the useState hook in your function. This allows us to write and return components that export a function instead of a class.

Using classes previously we would create components that looked like the following;

import React from 'react';

class Example extends React.Component {

constructor() {

super();

this.state = {

count: 0

};

}

incrementCount() {

const countPlusOne = this.state.count + 1;

this.setState({ count: countPlusOne });

}

render() {

return (

<div>

<p>You clicked {this.state.count} times</p>

<button onClick={() => { this.incrementCount() }}>

Click me

</button>

</div>

);

}

}

export default Example;

Now we can compose the same component using just a function and the useState hook.

// Example taken from https://reactjs.org/docs/hooks-intro.html

import React, { useState } from 'react';

function Example() {

// Declare a new state variable, which we'll call "count"

const [count, setCount] = useState(0);

return (

<div>

<p>You clicked {count} times</p>

<button onClick={() => setCount(count + 1)}>

Click me

</button>

</div>

);

}

export default Example;

As we can see from the last example, it is much easier to create a function for a component rather than using the class as we did in the previous example.

Summary

When I am writing JavaScript objects I prefer to use factory functions instead of classes. By using a factory function we no longer need to use the this keyword or the new keyword for creating a new object. There are still some reasons why you might want to continue to use classes in JavaScript. It is technically faster to use the new keyword over Object.create or Object.freeze, but we are talking about a few milliseconds. Eric Elliot has writen a number of good posts on the class keyword at the JavaScript Scene. I would recommend reading his post on the class keyword.