Author: David Fekke

Published: 7/12/2021

I will be doing a presentation to the JaxNode User Group on July 15th on the Async and Await feature in JavaScript. I have done some posts on Async and Await recently as well. One of the neat things about Async and Await is that it is finding it’s way into more and more programming languages.

Concurrency

Concurrency is becoming more and more important in today’s software. The reason is pretty simple. If you look at the processors that are being manufactured today, we are getting more and more transistors onto chips as well as more cores, but the chips are not really getting improved clock speeds. Clock speeds have been at a virtual standstill for the last decade or so.

If you look at some of the modern processors that we are getting in laptops and desktops, it is not uncommon to see eight or more cores. Apple’s M1 chip, which is meant to be their low end chip has eight CPU cores. AMD’s Rizen chip can come with as many as 32 cores.

CPU Cores allow us to run multiple processes at the same time. In the past developers could take advantage of multiple cores by spawning a new thread, doing some work, and then joining back to the main thread. This type of multi-threaded programming is a form of concurrent programming.

Concurrency is Hard

Spawning multiple threads also presents new types of challenges for developers. While threads can work independently of each other, they can also interact with each other. This can cause new kinds of bugs like race conditions and deadlocks.

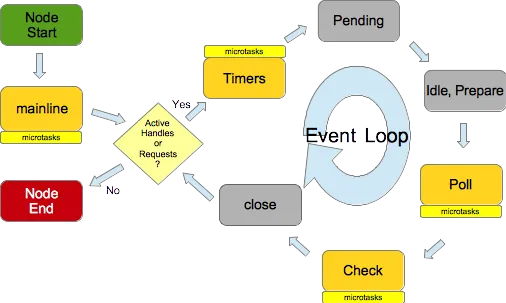

JavaScript is single-threaded, but we can still do concurrent programming in JavaScript. Node.js as an example uses a library called LibUV. LibUV takes advantage of the Node.js event loop. When a long running process is started, it will register a callback on the event loop freeing up Node.js to do other work. When the operation is completed, it triggers the callback completing the process.

Before we dive too deeply into the async/await keywords, we need to look at why these keywords are being added to existing programming languages. The reason is that in most programming languages that are popular today, concurrent programming involves the use of callback functions, blocks, delegates or pointer functions.

If you are not familiar with the async/await keywords in JavaScript, they allow you to explicitly designate a function as asynchronous, but write the function as if it were synchronous. This is extremely powerful because in the past the way you had to write asynchronous JavaScript involved using some form of callback. If you have multiple callbacks in a single function, this could devolve into a large callback structure that could be extremely difficult to read as in the example below;

fs.readdir(source, function (err, files) {

if (err) {

console.log('Error finding files: ' + err)

} else {

files.forEach(function (filename, fileIndex) {

console.log(filename)

gm(source + filename).size(function (err, values) {

if (err) {

console.log('Error identifying file size: ' + err)

} else {

console.log(filename + ' : ' + values)

aspect = (values.width / values.height)

widths.forEach(function (width, widthIndex) {

height = Math.round(width / aspect)

console.log('resizing ' + filename + 'to ' + height + 'x' + height)

this.resize(width, height).write(dest + 'w' + width + '_' + filename, function(err) {

if (err) console.log('Error writing file: ' + err)

})

}.bind(this))

}

})

})

}

})

This was improved somewhat with the arrival of Promises. Promises are created with a constructor function that takes two parameters, resolve and reject. The resolve parameter function is a callback for the successful result of the Promise while reject is the callback for the error.

const promise = new Promise(function(resolve, reject) {

// do a thing, possibly async, then…

if (/* everything turned out fine */) {

resolve("Stuff worked!");

}

else {

reject(Error("It broke"));

}

});

promise

.then(result => {

console.log(result);

}).catch(err => {

console.error(err);

});

While this is an improvement over Error first callbacks, it still does not have the elegance of a synchronous function.

Async and Await

Expressing a function as an asynchronous function essentially turns that function into a promise. As a matter of fact, Promises in JavaScript and Async functions are interchangeable. Lets’ take the node-fetch module as an example which is a promise. We can use it to retrieve data from a Rest API.

import fetch from 'node-fetch';

function getFact() {

fetch('https://cat-fact.herokuapp.com/facts/random')

.then(result => {

return result.json();

}).then(json => {

console.log(json.text);

});

}

getFact();

// This will return a random fact about a feline

Using async/await syntax, we can rewrite this function so that we do not have to pass or write callback functions;

import fetch from 'node-fetch';

const catFact = async () => {

const result = await fetch('https://cat-fact.herokuapp.com/facts/random');

const json = await result.json();

return json.text;

};

const fact = await catFact();

console.log(fact);

// This will return a random fact about a feline

The example above is a JavaScript module, so I can write my top level JavaScript to use the await keyword without having to use it inside of a function marked async.

The result of having refactored this is that I can actually use the return keyword to pass a result. This feature makes developers much more productive. It makes the code easier to read, and it also makes it easier to debug. Plus I can take any async function in JavaScript and execute it like it were a Promise.

catFact().then(fact => { console.log(fact) });

JavaScript was not First

JavaScript was not the first language to use async and await. There were multiple functional languages that used these keywords before JavaScript including Haskell and F#.

open System

open System.IO

let printTotalFileBytes path =

async {

let! bytes = File.ReadAllBytesAsync(path) |> Async.AwaitTask

let fileName = Path.GetFileName(path)

printfn $"File {fileName} has %d{bytes.Length} bytes"

}

[<EntryPoint>]

let main argv =

printTotalFileBytes "path-to-file.txt"

|> Async.RunSynchronously

Console.Read() |> ignore

0

Anders Hejlsberg, the original architect of C# at Microsoft, took inspiration from this form of expressive concurrency, and added it to C# around 2011. C# does not have Promises, but it does have Tasks. You can use the Task type with the async/await keywords to make your C# methods asynchronous.

private static async Task<int> DownloadDocsMainPageAsync()

{

Console.WriteLine($"{nameof(DownloadDocsMainPageAsync)}: About to start downloading.");

var client = new HttpClient();

byte[] content = await client.GetByteArrayAsync("https://docs.microsoft.com/en-us/");

Console.WriteLine($"{nameof(DownloadDocsMainPageAsync)}: Finished downloading.");

return content.Length;

}

If you need to return a specific type from your method, the Task is a generic type, and you can specify a certain type you would like returned from your Task<T>.

Rust

Rust recently added the async and await keywords to the language as a way of handling Futures. Futures in Rust are very similar to Promises in JavaScript. They can be polled to see if the Future is still pending, and once it is ready handle the result.

async fn example(min_len: usize) -> String {

let content = async_read_file("mycatdata.txt").await;

if content.len() < min_len {

content + &async_read_file("myfelinedata.txt").await

} else {

content

}

}

Swift

As of Swift version 5.5, async/await has found its way into the Language. iOS and iPadOS developers will start to be able to use these new concurrent features in iOS/iPadOS 15 this Fall.

This was originally proposed by Chris Lattner back in 2017 in his famous Swift Concurrency Manifesto. Previously Swift developers did asynchronous programming using Grand Central Dispatch, or GCD for short. This involved using trailing closures, essentially the same thing as a callback in Swift.

Apple has been able to add concurrency into the Swift by adding async/await keywords as well as other features such as actors.

func processImageData1() async -> Image {

let dataResource = await loadWebResource("dataprofile.txt")

let imageResource = await loadWebResource("imagedata.dat")

let imageTmp = await decodeImage(dataResource, imageResource)

let imageResult = await dewarpAndCleanupImage(imageTmp)

return imageResult

}

Swift’s implementation is a little different from the other languages we have seen because the async keyword trails the func name instead of leading like it does in JavaScript. Swift also allows developers to spawn multiple threads inside the body of our function by using the async keyword in front of the variable assignment.

async let firstPhoto = downloadPhoto(named: photoNames[0])

async let secondPhoto = downloadPhoto(named: photoNames[1])

async let thirdPhoto = downloadPhoto(named: photoNames[2])

let photos = await [firstPhoto, secondPhoto, thirdPhoto]

show(photos)

I am sure iOS and MacOS developers cannot wait to start using these concurrent language features in their apps.

Conclusion

Pretty soon if your preferred programming language does not have async/await, it probably will soon. The one exception to this is probably Java, but new features always seem to come last to Java.

I am extremely happy to see async/await make it into more languages. It has certainly made me more productive as a software engineer.